Sensory hell and medical harm

My sister’s experience of very severe ME in the NHS

First of all, a quick reminder that nominations are still open for our 2025 Advent Calendar! If you’d like to thank someone who has been #ThereForME this year, just fill out our form here (nominations will close on October 26).

Today’s guest post is from Rosie Barrett. Rosie, 31, is a full-time carer for her younger sister, Alice. She moved back to her parents’ house when Alice first became bedbound in 2022. Rosie made a #FundThePlan video earlier this year and has given TV interviews to help raise awareness. Her blog today echoes many of the themes from our previous collaboration with Patient Safety Learning which focused on the challenges faced by people with ME when accessing healthcare.

My sister Alice has very severe Myalgic Encephalomyelitis (ME), along with Postural Orthostatic Tachycardia Syndrome (POTS) and Mast Cell Activation Syndrome (MCAS). She has lived with ME for around six years, but the last three have been devastating – she is now completely bedbound, has an indwelling catheter and is PEG-fed (through a feeding tube into her stomach). For a while, she also received IV fluids at home through a PICC line: this is a line that can be in place longer-term, allowing treatments to be delivered directly into the vein. But that stopped after the line broke. The risks of travelling to hospital for a new one were simply too great.

Before ME, Alice had no health issues. She was thriving – she’d just graduated from Newcastle University, moved to Bristol and got her first job. She was active, optimistic and excited for the future. ME took all of that from her. Eventually, she had to move back home because she could no longer care for herself.

Hospital admission

In February 2023, Alice was hospitalised. Swallowing became too much for her due to the energy involved and she was unable to take on enough calories. She became malnourished and needed lifesaving nutrition. Alice agreed to be hospitalised reluctantly. She knew she needed help but also knew how damaging a hospital environment would be for her symptoms. She faced two battles: the first for her physical survival, the second against the environment itself.

Hospitals are simply not set up for someone with ME: beeping machines, vibrating trolleys in the corridors, bright overhead lighting, strong smells from perfumes and cleaning products, noisy conversations from other patients and staff, weekly fire alarm testing, observations and interactions with medical staff (even though we were lucky and the nursing staff tried their best).

Her poor toleration of and sensitivity to sound (hyperacusis), light (photophobia), and movement (allodynia) made every moment a fresh trauma. Each sensory assault triggered post-exertional malaise (PEM), the hallmark symptom of ME – a worsening of symptoms following even minor physical or mental activity. Her baseline deteriorated rapidly. Her neurological symptoms worsened. After a three-month admission she left the hospital with the PEG tube she needed but with significantly more limited functionality than when she went in.

Hospitals must do better

Hospitals should be places of healing – but for people with severe ME, they are often sources of harm.

The NHS urgently needs to create sensory-safe spaces. These aren’t ‘nice-to-haves’ – they are essential for people with ME and others with complex neurological conditions. The one-size-fits-all approach to hospital care simply does not work for patients like Alice.

Too often, people with ME avoid hospitals altogether — only going in life-or-death situations — knowing full well that admission will likely make them worse. Accessibility is about more than ramps and lifts. It’s also about reducing sensory and environmental harm.

Adaptations that are needed include:

ME-specific or sensory-sensitive wards

Side rooms with blackout blinds and dimmable lights

Soundproofing or vibration-reducing flooring

Fragrance-free policies

Staff trained to speak quietly, to limit physical touch, and to understand PEM

Reduced and adapted interactions tailored to the patient’s needs

Space for family members and known carers to stay with the patient, as they are best placed to provide daily care for their person with ME in a way that doesn’t exacerbate symptoms

Home

When Alice came home after her hospital stay, she was unable to go back upstairs to her bedroom. The stairs have a bend in them and sitting her up – even briefly – wasn’t an option due to severe POTS. So we set up the sitting room downstairs as her new room. We’ve done everything we can to adapt the room to her extreme sensory needs.

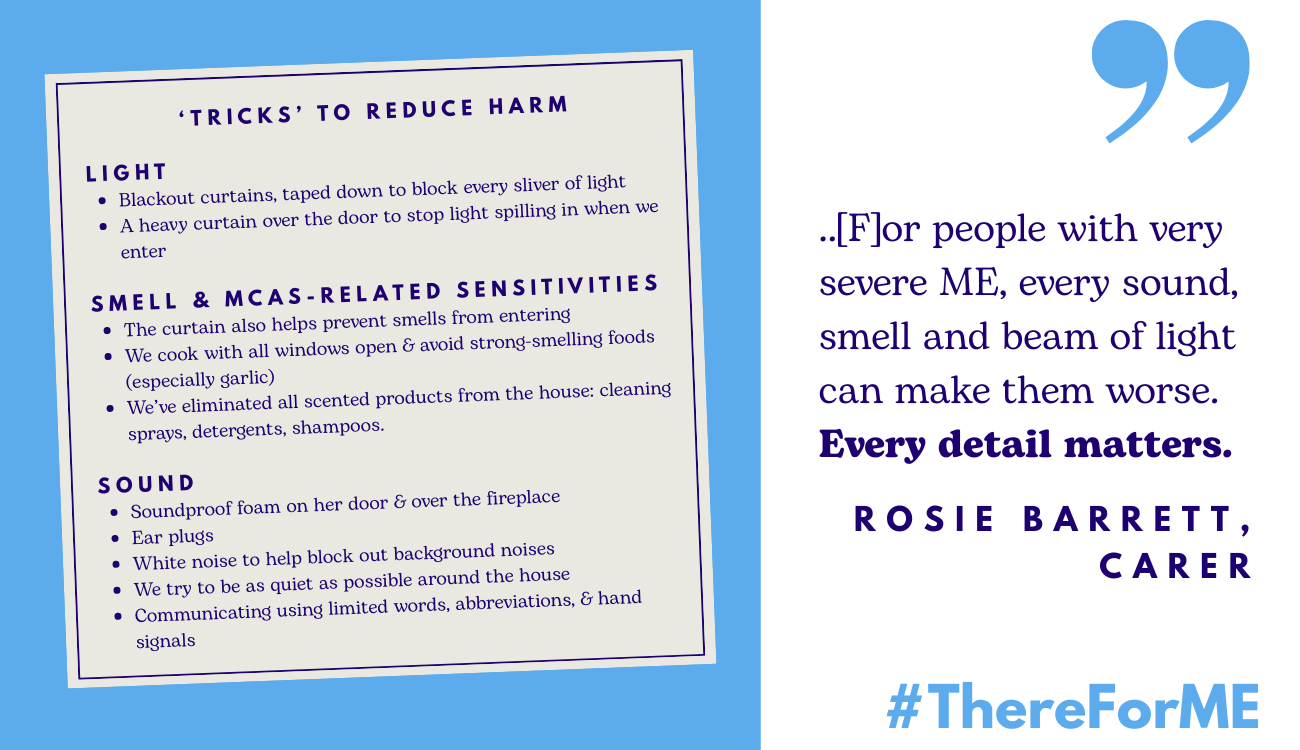

Everyone I know who supports someone with severe/very severe ME has their own set of ‘tricks’ to reduce harm. Here are some of ours:

Light:

Blackout curtains, taped down to block every sliver of light

A heavy curtain over the door to stop light spilling in when we enter

Smell and MCAS-related sensitivities:

The curtain also helps prevent smells from entering

We cook with all windows open and avoid strong-smelling foods (especially garlic)

We’ve eliminated all scented products from the house: cleaning sprays, detergents, shampoos. We only use products that are unscented and that don’t trigger Alice’s MCAS symptoms

Sound:

Soundproof foam on her door and over the fireplace (to minimise the noise of wind down the chimney)

Ear plugs

White noise to help block out background noises

We try to be as quiet as possible around the house

Communicating with Alice using limited words, abbreviations, and hand signals

This level of adaptation might sound extreme, even hard to imagine. But for people with very severe ME, every sound, smell and beam of light can make them worse. Every detail matters. These sensitivities must be better understood – by families, by the public, and most importantly, by health professionals.

Thinking differently

ME forces you to think differently, to problem-solve, to compromise, to reimagine daily life in a way most people will never have to. It also highlights how ill-equipped our health and social care systems are for patients with complex, poorly understood conditions.

It’s not just hospitals that need to change. Community care must evolve too. We need:

Sensory-safe spaces in GP surgeries

Home-based or virtual care options

Training for NHS community teams on sensory overload and PEM

Policies that treat environmental triggers as accessibility issues, not just patient preferences

Before Alice was in hospital, we had difficulties with health professionals in the community. Now, however, we are lucky that the few health professionals that do have direct involvement with Alice take measures to accommodate her needs. They change into unscented scrubs and make a conscious effort to not use any scented products on the day of their visit. They are happy for us to be Alice’s advocates to minimise any unneeded interaction with her. They see Alice in dimmed light. If they need to speak to Alice, they either pass a message to her through us or they make sure to speak quietly and carefully to her.

What being #ThereForME really means

It’s not enough for the NHS to have a one-size-fits-all model for ME – it is essential that it is flexible enough to accommodate patients’ individual care needs. Until then, people with ME will continue to suffer needlessly, and potentially deteriorate, when trying to access healthcare. Indeed, many will avoid it entirely.

It’s a dilemma no one should have to face: whether or not to access much-needed medical care, when without adequate adaptations that care puts them at risk of further harm.

Thanks for sharing this experience. I have moderate MECFS and aware of how a) 'lucky' I am to be so and b) know that others aren't. NHS must do better!

Absolutely spot on. And the other nightmare I've experienced during hospital stays over the past few years, is that they're putting severe dementia patients on the wards along with everyone else. My last stay was especially hellish and the elderly ladies, both in the late stages of dementia, screamed, shouted, howled, & swore, 24/7. My nervous system was overwhelmed and symptoms went wild, and when I told the nursing staff that I was struggling, they wanted to give me more and more meds to try and calm my symptoms, when what I needed was absolute quiet. Even headphones didn't help. I complained because other patients on the wards I was on were crying out and begging these ladies to keep quiet, and so the cacophony of noise was crazy. I was very, very ill, but discharged myself out of fear of being put into a full-blown relapse. 😕😢😠