Campaign update #30: Six months since the publication of the Final Delivery Plan for ME

January 22nd marked six months since the publication of the government’s new Final Delivery Plan for ME. What progress has been made? Are there signs the plan is making a difference? Today we’re taking a whistlestop tour of the latest developments in three priority areas.

Improving care for severe and very severe ME

As we highlighted when the Final Delivery Plan was published, it contains few concrete solutions. Severe ME was notably absent from plans to improve NHS provision, while the plan committed only to “explore” whether a specialised service should be prescribed for very severe ME.

Six months on, there’s still no clarity on how the NHS plans to handle those with severe or very severe ME, which remain absent from a new service specification in development for mild and moderate ME (an NHS England template which local integrated care boards will be encouraged to use when commissioning services). To date, this new specification has been the only significant activity in terms of service improvements.

Regarding very severe ME, the Department of Health and Social Care has “commenced discussions with NHS England on how best to take forward” the plan’s action to explore specialised service provision. While the Department claims to be “taking specific steps to ensure that patients with severe and very severe ME/CFS are not overlooked”, there has been little concrete action to reassure those affected that this is more than empty words.

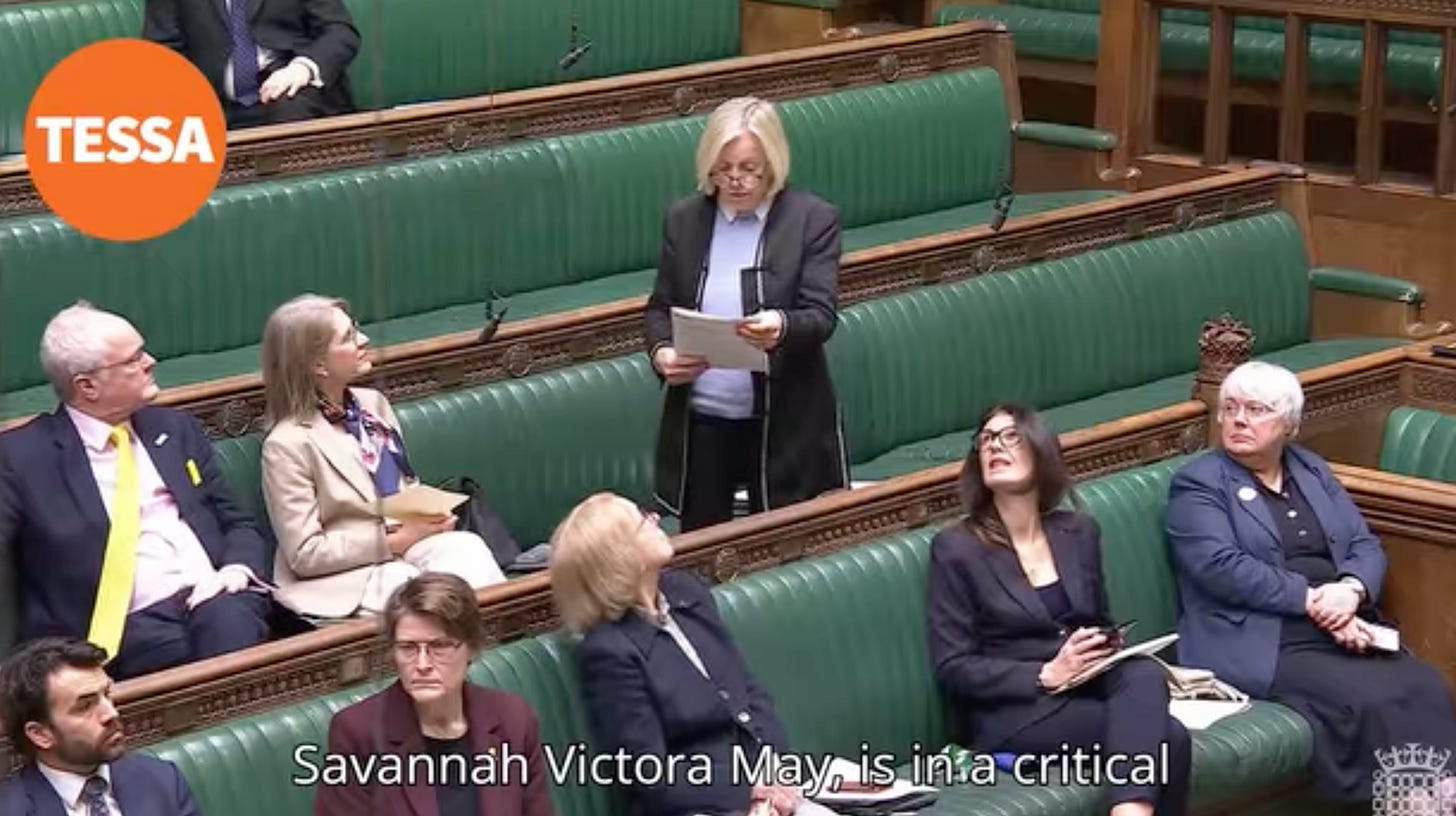

This matters because, as raised by Tessa Munt MP (the new Chair of the APPG on ME), patients are suffering - and indeed, lives are at risk - while the Department prevaricates. Despite Ashley Dalton’s promise six months ago to make avoidable deaths of people with ME “never events”, in practice nothing has changed since, nor is there any sign that it is likely to. Tessa raised the case of Savannah Victora-May in London’s Queen Elizabeth Hospital, whose condition has deteriorated rapidly, leaving her unable to eat or drink. Savannah’s case was covered in The Times yesterday, which highlighted failures to follow the 2021 NICE Guideline and fears that Savannah may die without proper care.

While we’re an optimistic campaign which always tries to look for the rays of hope, we’re giving the plan’s impact in this area a shameful 0/5.

Boosting education and training

The public consultation which informed the Final Delivery Plan called for training on ME to be made mandatory. Unfortunately, this didn’t make it into the plan. Instead, a series of optional NHS e-learnings became the cornerstone of efforts to educate professionals across health and social care, combat misperceptions and address stigma.

We’ll start with the positive. Six months on, all of the planned e-learnings have been published, including a module on severe ME. The downside? A recent Freedom of Information request (kudos to @Lucibee.bsky.social) revealed that to date uptake has been, to put it mildly, disappointing. So far:

371 people, including 227 working in the NHS, have completed the introductory module (released in May 2024)

101 people, including 74 in the NHS, have completed a module focused on community care (released in January 2025)

Less than 50 people, including 33 in the NHS, have completed the most recent module on severe ME (released in September 2025)

For the data crunchers out there, that’s 11 NHS workers per month completing the introductory e-learning and 7 per month undertaking training on severe ME. With close to 800,000 professionally qualified clinical staff and GPs in the NHS in England, that’s a mere 5,942 years until all of them have completed their introductory training on ME. To give you an idea of what better looks like: in its first year, the Oliver McGowan Mandatory Training on learning disability and autism was completed by close to three quarters of a million.

We’re giving this one a feeble 1/5.

Accelerating research

While the Final Delivery Plan acknowledged the need to expand ME research, it offered little concrete new funding. Key in moving this ambition forwards was a “showcase event” for post-acute infection conditions research, including ME and long COVID, which aimed to discuss recent evidence and “recognise the importance” of research in these areas.

The event was held last November, with a summary published recently. Presentations spanned Professors Altmann, Banerjee, Sivan and Ponting, who between them highlighted the challenges posed by lack of biomarkers, inequalities in care and key genetic signals. Afterwards, roundtable discussions covered themes including attracting new researchers to the field, persistent funding challenges and the need to enhance collaboration.

So far so good. However, the key marker of success in this area was always going to be not the event itself, but whether it led to a change in the scale of funding. So far, no new significant funding has materialised.

Notably, however, charities and researchers have since shown they intend to move ahead regardless of the slow pace of government action. In December, the ME Association announced it would be investing £1.1 million into the Rosetta Stone study, led by Professors Danny Altmann and Rosemary Boyton and colleagues at Imperial College London. The study will focus on the immunological profiles of ME and Long Covid, aiming to learn about underlying mechanisms through analysis of shared pathways.

Elsewhere, the ME/CFS alliance recently announced an event in Winchester in early March, bringing together eminent researchers from the UK and around the world to discuss the next strategic steps for ME research.

We’re giving this one a 2/5, but with a nod to the researchers and campaigners who have been doing the heavy lifting. We’re hoping to soon see the UK government following suit (your regular reminder here that the German government recently officially launched its ten-year initiative to tackle post-infectious diseases like ME, to the tune of 500 million Euros).

Looking ahead

It’s important to say here that change happens slowly, particularly in organisational behemoths like the NHS (or, as the saying goes: slowly, slowly and then all at once). Nonetheless, looking back, the scorecard from the first six months of the Delivery Plan is pretty disappointing.

Of course, people with ME are used to a slow pace of change and - particularly for those who’ve been in this much longer than we have - seeing the same debates repeated through the generations (does this early 90s clip from Adam, AKA Broken Battery, feel familiar?)

We’ll say it again, as we always do: people with ME deserve so much better. Here’s hoping the next six months of the Delivery Plan bring more for us to celebrate.

We’ll see you next time.